Australia’s economic growth has been increasingly reliant on population rather than real reforms to improve productivity and living standards.

It has been deteriorating for several decades through governments of all types.

Here is the Big Picture you will not find anywhere else.

Getting behind the headlines

Australia’s official economic growth numbers for the 2023 calendar year were released yesterday, so it’s a good opportunity to see how we are progressing as a nation (economically anyway).

Media headlines focus on the headline growth number (we will get to it in a moment). They don’t tend to focus on where the growth came from, which is far more important.

Growth in a country’s overall economic pie comes from two main sources:

(a) growth in population (more people producing, earning, and spending the same per person as last year); and

(b) growth in output, income, and spending per person – which drives growth in living standards

In a recent story, I highlighted the fact that Australia has (and has had for two centuries) the highest population growth rate of any country outside of Africa, and is still the most sparsely populated.

See: Australia’s extraordinary population-led growth

Today’s story highlights the fact that Australia’s economic growth has been increasingly reliant on population rather than real reforms to improve productivity and living standards.

Population -v- Productivity growth

Of these two components of growth, the second is far more important and desirable, because it contributes to higher living standards per person, through higher levels of incomes and wealth per person, better schooling, and health care, etc.

On the other hand, population growth doesn’t increase living standards per person. Economic growth through population growth alone just means more traffic, more crowded schools and hospitals, more pollution, more waste, more construction, more noise.

The problem is that most of Australia’s overall economic growth has come from population growth, rather than productivity growth. It has been getting worse for decades, and it is still getting worse.

2023: Slow growth after inflation

First to the latest numbers. In 2023, Australia’s overall economic pie grew by a healthy-looking 5.6% in nominal terms (before inflation), but overall price inflation of 3.4% reduced the ‘real’ growth rate to just 2.1%.

Aside from the negative growth of -2.1% in 2020 (Covid lockdown recession), the 2.1% real growth rate in 2023 was the slowest calendar year growth rate since 2009 (2.0% in the GFC).

The main factors slowing growth in 2023 were slowdowns in spending by consumers and business, and lower construction activity, due largely to increases in interest costs.

‘GDP’ (‘Gross Domestic Product’) is the most widely used measure of a country’s total output (production), which more or less equates to total national income, and total spending (expenditure).

We went backwards per person

Despite positive ‘real’ growth in 2023, Australia’s population grew faster than the economic pie, so the share of the economic pie per person shrank.

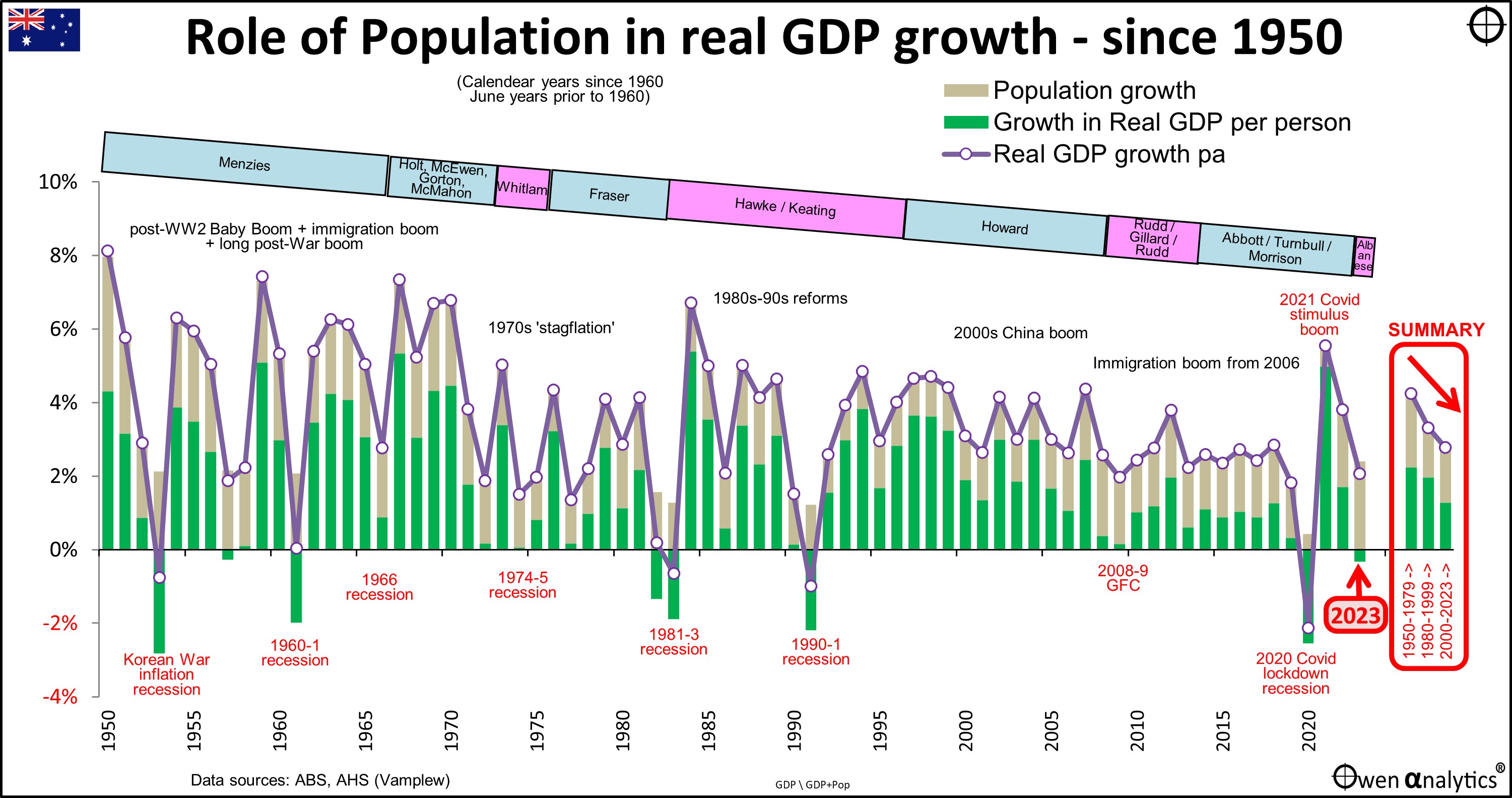

The negative growth in GDP per person in 2023 is highlighted near the far right in the above chart, and we can see negative GDP per person occurs mainly in recessions.

The population grew by 2.5% in 2023 from 26.305 million to 26.959 million, but real GDP grew by just 2.1% (from $2,379,637 million to $2,428,737 million, so GDP per person fell by -0.4% from $90,464 to $90,089 per person.

Aside from 2020 (Covid lockdown recession), 2023 was the first time GDP per person went backwards since 1991, 1983, and 1953 (all recession years).

Long slow decline in growth rates since 1950

The first chart above shows annual growth in Australia’s real GDP (purple line), population growth (grey bars), and growth in GDP per person (green bars), each year since 1950.

The most obvious feature of the above chart is the steady decline in economic growth rates in Australia over many decades (only punctuated briefly by recessions).

This steady decline has persisted through all governments from both sides of politics, which are shown on the chart.

Some governments have been better than others of course.

Without going into politics, the first observation would be that all governments of all persuasions, from the very first years of British settlement, have generally been pro-growth, pro-resource exploitation, pro-immigration, pro-individual freedoms, and (mostly) pro-business.

We tend to take these things for granted here, but other countries have not had the same success. Australia’s prosperity has not just been resource abundance - there are plenty of resource rich countries that are economic basket cases.

A second general observation is that Australia’s economic performance has largely been shaped by global events – including the World Wars, the post-War baby booms, oil supply shocks, major economic booms and recessions, financial bubbles and busts, etc.

The domestic impacts of these global events were shaped to some extent by local political decisions, but the big drivers of most of our economic cycles and events have been global forces.

Summary of shrinking growth rates since 1950

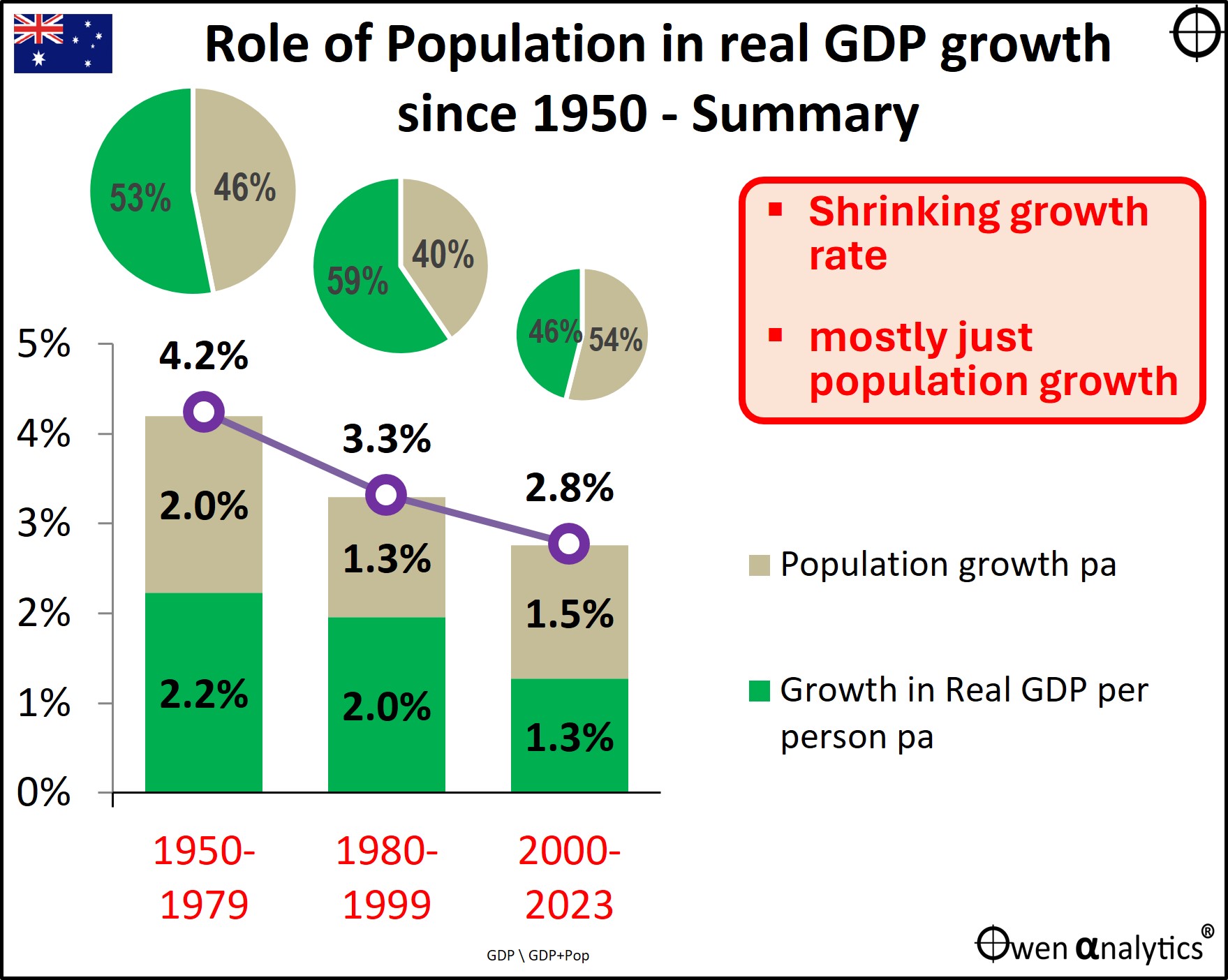

The next chart expands the Summary section in the right section of the main chart above.

Rates of overall economic growth in Australia have declined substantially - from 4.2% pa in the 1950s to 1970s, down to 3.3% pa in the 1980s and 1990s, and now down to just 2.8% pa so far this century.

Critically, more than half of the growth in the total economic pie is now just coming from population growth.

Since British settlement – by decade

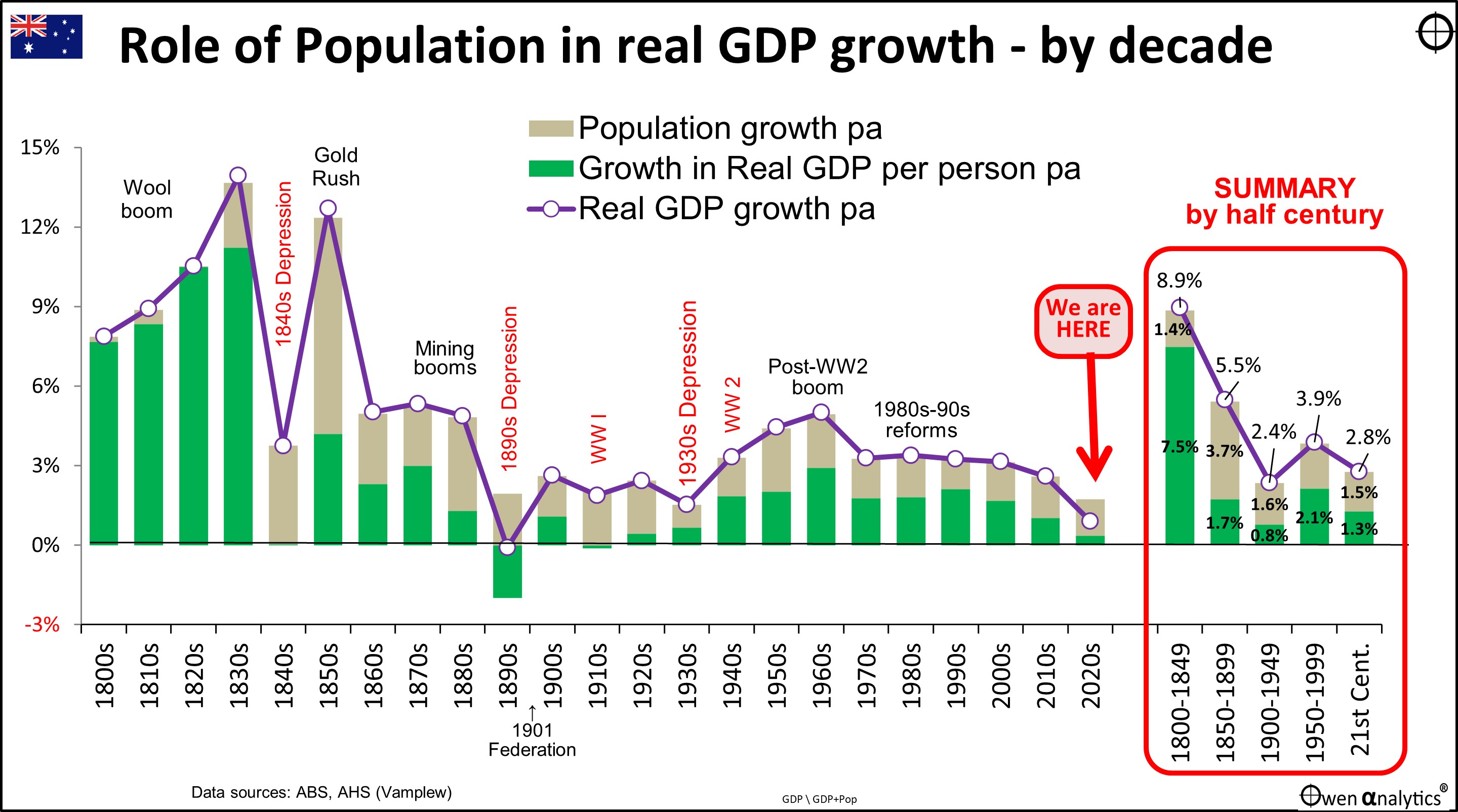

For completeness, here is the picture since 1800, from the early days of British settlement.

Nineteenth century

The first half of the nineteenth century look like very high growth numbers – but they were starting from a very small base, in both population and output per person.

The early years of settlement were very harsh, but prospects improved dramatically with the rapid expansion of sheep farming to supply wool to Britain’s textile boom in the early days of Britain’s industrial revolution, plus discoveries of coal in Newcastle and copper east of Adelaide. The 1930s boom collapsed in the (global and local) 1840s depression and banking crisis.

The second half of the nineteenth century was Australia became the richest country on the planet, thanks to agriculture (further expansion of wool, then wheat, and other crops), mining (gold, silver, base metals), and a property/finance boom that collapsed in the (global and local) 1890s depression and banking crisis.

Twentieth century

The first half of the twentieth century had much lower economic growth rates – for both population and growth per person.

The main contributing factors to the lower growth were the two World Wars, the 1930s Depression, and also the high tariff barriers and controls erected to protect local industries. Our ‘self-reliance’ drive was necessitated by the World Wars, but protection was retained far too high and for too long, leaving the economy inflexible, over-regulated, centralised, with high costs, high taxes, and low productivity.

The second half of the twentieth century experienced the highest rates of growth per person (growth in living standards) since the first half of the nineteenth century.

High rates of growth in the post-WW2 boom in the 1950s and 1960s, but this ended in the ‘stagflation’ 1970s, a global phenomenon made worse by governments here, especially under Whitlam.

Growth rates were lifted once again after the radical 1980s and 1990s economic reforms of the Hawke/Keating governments.

These included floating the dollar, removal of capital controls, deregulating banking, opening to foreign competition, privatising government businesses, reducing tariff protection, improving competition laws, enterprise bargaining, tax reform, central bank independence, compulsory ‘super’.

In the Howard years, the reforms were extended but much of the windfall gains from the China/mining boom were squandered on middle class welfare, which have been politically near impossible to wind back (although some of the gains were ‘banked’ by paying off the national debt and setting up the Future Fund).

Prospects for reforms to raise productivity and living standards?

The past sixteen years have been a whirlwind of revolving door governments that did not demonstrate much ability to think beyond the daily news cycle or the next leadership challenge.

The current government is clearly moving back in the direction of centralised controls, reduced workplace flexibility, increased union power, national strikes, productivity-free wage rises, subsidising and picking ‘winners’, and it is squandering temporary windful mining gains on expanding government spending rather than paying off debt.

Population growth easier than hard reforms

Genuine economic reforms are hard work and politically risky.

Deep and radical government reforms in the past have only been made when the nation faced nightmare conditions – like double digit inflation and/or unemployment, or military attacks on our soil. Making far-reaching and unpopular decisions was a necessity, not an option.

Compared to traumatic conditions in the past that triggered deep and lasting changes, conditions today are very mild.

Instead, to keep the headline numbers growing - like jobs numbers and company revenues and profits, opting for population growth is a much easier path. The place is still virtually empty!

This vast, sparsely populated rock we live on seems to be packed with enormous reserves of an ever-increasing array of raw materials that other people in other countries want to buy from us to turn them into useful things they then sell back to us at hundreds of times the price we got for it in the first place.

We need more people to dig it all up, and we need more people to defend the rock.

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions!

See also: