In 2021 and 2022, when the prices of nickel and nickel explorers/miners were soaring, my inbox was flooded with emails asking which nickel stock(s) to jump into.

The long list of hot stocks included: Independence Group (IGO), Western Areas (WSA), AusQuest (AQD), Focus Minerals (FML), Mincor (MCR), Panoramic (PAN), Ardea Resources (ARL), Australian Mines (AUZ), Barra Resources (BAR), and even one called Poseidon Nickel (POS) – we will get to that later.

Since all mining booms follow a familiar pattern, and end the same way for the same reasons, I responded by referring to my story about the mother of all nickel boom-busts – Poseidon, involving the very same nickel mines.

How’s a one-year gain of 46,000% sound?

‘Poseidon’ was a mining exploration company named after the Greek God of the Seas, and also the name of the 1906 Melbourne Cup winning race horse.

Poseidon, the company, certainly turned out to be a gamble, making a fortune for insiders and a few lucky punters, but ending in a sea of red ink for thousands of others who jumped on the bandwaggon hoping to make a quick buck - or perhaps thinking ‘This time is different!’

Corporate skulduggery at its finest

The Poseidon boom and bust became the poster-child for corporate skulduggery by directors, promoters, and brokers in the 1960s that led to a host of legislative reforms and regulations including the criminalisation of insider trading.

Unfortunately insider trading, stock ramping, and fraudulent mining reports are still with us today despite decades of regulation.

Poseidon was certainly not the worst offender in the late 1960s nickel boom. It was different to most in that it actually had a real mine with real metal in it. Many outright fraudulent companies had neither.

Poseidon’s share price shot up by 46,000% in 1969. At the height of the frenzy in February 1970, the company had a market value of $700m, three times the size of the Australia’s largest listed bank at that time, the Bank of NSW (now called Westpac).

Unfortunately Poseidon never made a profit nor paid a dividend. It ran out of money and went into receivership just five years later.

Why nickel?

Nickel was a hot commodity in the late 1960s. As the key ingredient in making stainless steel and armour plating for military equipment, its strong demand growth was driven by the Vietnam War and also by the aerospace boom that peaked with the Apollo 11 moon landing in July 1969.

There is nothing like a moon landing to spur public imagination and enthusiasm (just ask Elon)!

Today the driver of hot demand is the ‘battery metals’ boom in the race to electrify everything, especially motor vehicles. In both booms, the demand story was real and strong, but the demand side is not where the action is.

Supply-side story – same old, same old

As with most mining cycles, supply was not able to keep up with demand because of the long lead times for exploration, development and bringing new mines into production.

Demand growth for nickel in the 1960s was running down stockpiles in Russia and the US (stockpiled from the over-production glut in the previous cycle).

While prices were rising, the catalyst for the bubble was a miners’ strike at the two largest nickel producers in the world (Inco and Falconbridge, both in Canada). The miners’ strikes quickly brought the global supply of nickel to a virtual halt in late 1969.

Commodities prices

Just like today, there were two prices for many metals – a long-term contract price (‘producer price’), on which long term supply contracts were based, and a ‘free market’ or ‘spot’ price, which was effectively a real-time barrometer of investor sentiment about supply-demand imbalances.

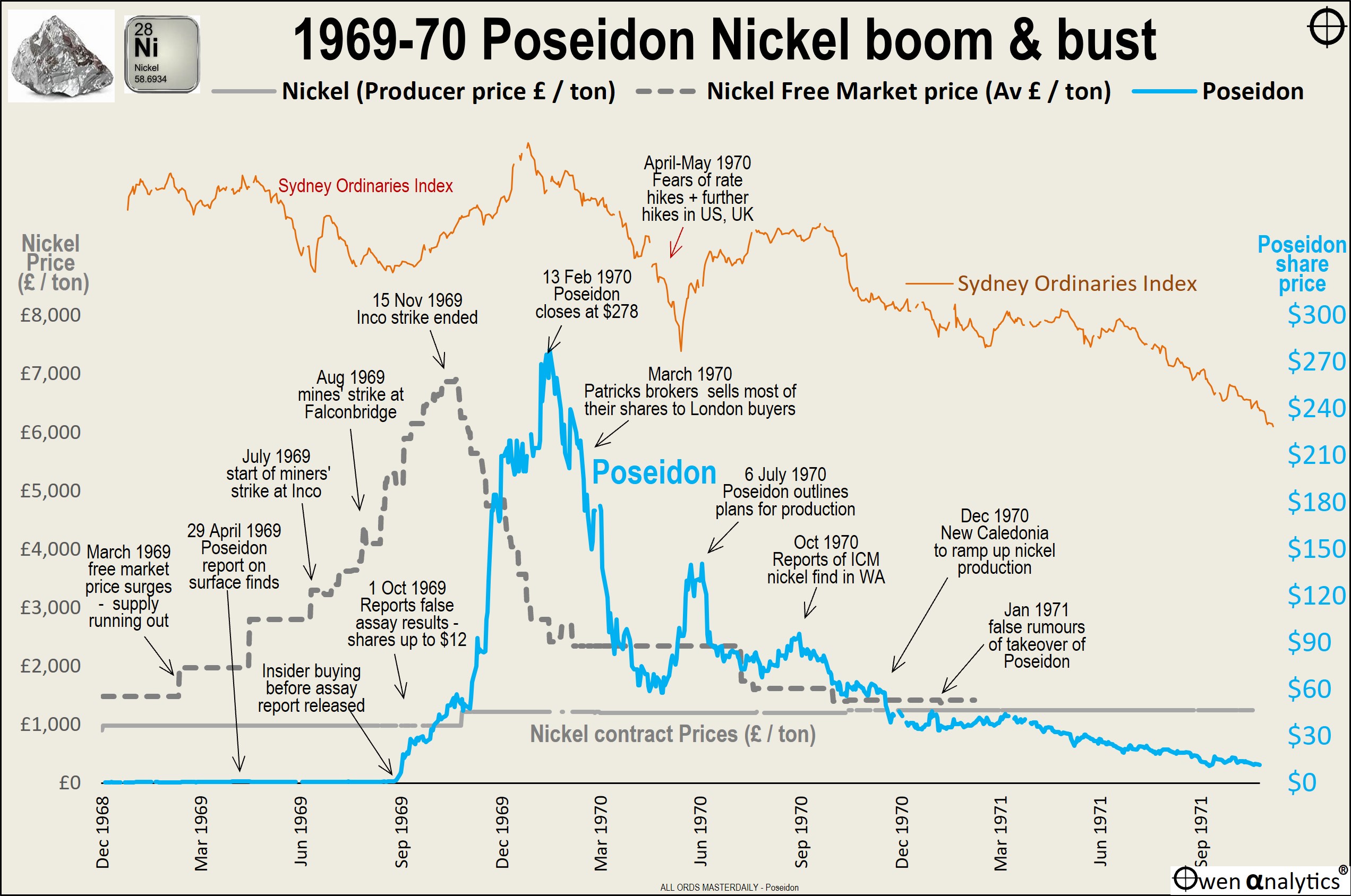

The chart shows the long term contract price of nickel (solid grey line), rising steadily over time as contracts were renewed between major producers and buyers.

The heavy grey dotted line is the ‘free market price’ (outside of long term contracts). This suddenly shot up seven-fold after the miners’ strikes in Canada.

The price hike triggered a surge of new interest in exploration. This quickly led to a miraculous spate of new nickel ‘finds’ being reported, and an equally miraculous spate of new companies hastily thrown together by promoters and brokers to cash in on the nickel fever.

The Poseidon adventure

Poseidon was formed in 1958 and listed on the Adelaide exchange. It started out with a low grade, unprofitable wolfram (tungsten) mine in NT. When it ran out of money the virtually empty company was picked up by Sydney share trader Boris Ganke (including picking up 50,000 shares at 2 cents per share at an auction of forfeited part-paid shares), and Adelaide mining engineer/broker Norm Shierlaw in 1968.

To cash in on the nickel fever created by the sudden price rise, they quickly raised more money and started exploring for nickel in the area around Western Mining’s existing nickel find in Kambalda in WA.

On 29 April 1969 they released a report to the Adelaide stock exchange announcing the discovered nickel in surface samples near Mt Windarra, 350km north of the Kalgoorlie gold fields, and they were to start drilling for underground samples. The share price jumped from $0.85 to $1.10 on the news.

They also listed the stock on the Sydney exchange in order to lure in a larger pool of ‘investors’ (gullible punters).

Fraudulent drilling reports

On 1st October 1969 the directors released a misleading report on the drilling samples to the exchange, that greatly exaggerated the actual results.

In the days leading up to the release the directors and their associates had bought up shares from unsuspecting shareholders, which pushed the share price from $0.85 at the start of September to $1.90 by Friday 26th September. Rumours of insider buying pushed the price up to $5.60 on the 29th and $7 on the 30th , just before the report.

When the false drilling report was released on 1st October, the share price shot up to $12.

Bingo! – instant riches for the insiders. Insider trading was not illegal back then!

Frenzied panic buying and further bullish reports pushed the share price up to $38 by the end of October.

‘FOMO’ frenzy un-hinges from fundamental supply story

From the middle of November, nickel spot prices had started to fall back after the Canadian miners’ strike was resolved on the 15th , but Poseidon’s share price kept rising past $50, fuelled by further bullish drilling reports and rumours of share buying from London.

Investor confidence was also buoyed by the Federal election on 25th October, when conservative John Gorton defeated the radical left wing Gough Whitlam.

The FOMO frenzy had un-hinged from the fundamental supply story, and people’s bidding hands became un-hinged from their brains.

Despite falling nickel prices, Poseidon's share price kept surging upward. It cracked $100 on 17th December, $150 on 22nd , and $185 on Christmas Eve 1969.

The Sydney Stock Exchange even opened the market on 29th, 30th and 31st December (normally trading holidays), so hoards of frenzied punters could throw even more money at the craze.

This sent the share price up to $210 on the 31th December 1969. From $0.48 at start of the year, that’s a one-year price gain of 46,300%.

Meanwhile, Western Mining Corp, the largest nickel producer in Australia, was up only 53% in 1969 (from $11.20 to $17.20).

But why settle for a lousy 53% gain from a real miner with real production when you can get thousands of per cent gains with blue sky!

UK buying frenzy

As is often the case with Australian companies, a large share of the gullible punters were in the UK. The further away the targets are, the more exotic and exciting the prize appears, and easier it is go get them to part with their money!

(It was similar in the WA gold booms in the 1890s and 1930s, where the biggest losers were faraway UK punters.)

One London broking house, Panmure Gordon & Co, valued Poseidon at ‘conservatively worth $500 and more optimistically $582’ per share!

‘The Times’ of London even named Poseidon: ‘the share of the year – if not of all time!’ (23 November 1969).

Yep, conservative lot, those Brits! However, ‘The Times’, in the same article, did go on to warn of:

‘. . . a more than adequate opportunity for the private investor to make a loss.”

The peak share price paid for Poseidon was $280 per share intra-day on 5 February 1970, and the peak daily closing price was $278 on Friday 13th February. Surely a bad omen!

Market-wide mania

The frenzy was not confined to Poseidon. Nickel mania spread to other nickel explorers, then to other mineral stocks generally, and then to a whole host of other stocks that had nothing to do with mining or nickel.

All up, 242 new floats raised $443m in cash in the late 1960s mining boom. (1.5% of GDP at the time, which is the equivalent of $35b today).

Most disappeared worthless. The money didn’t ‘disappear’ of course - most of it ended up in the pockets of shifty promoters and brokers.

Although Poseidon’s shares were not included in the stock market indexes of the day, the Poseidon boom lifted the broad indexes of Australian exchanges to new highs in late 1969 and January 1970, while stock markets in the US and UK were falling heavily (due to interest rate hikes in the US, UK, and Europe).

This was one of the very rare occasions when Australian shares did not follow the US market down.

Collapse

The boom didn’t last long of course. Poseidon’s share price collapsed during 1970 along with the rest of the mining market and the broader stock market across the board.

By October 1971, Poseidon’s share price was back down below what it was in October 1969 and it ended up in receivership, worth nothing.

Why the share price collapse?

First, the price of nickel collapsed. When the Canadian miners’ strikes ended in November 1969, the free market price quickly fell back to pre-crisis levels.

The nickel price kept falling as new sources of nickel were discovered – in WA, New Caledonia, and around the world, thanks to the burst of exploration triggered by the temporary 1969 price surge.

Second, the Poseidon nickel find turned out to be far less than the initial inflated reports. The ore turned out to be only 1.5% nickel instead of the claimed 3.5% in the false drilling reports.

Third, the company ran out of money trying to develop the mine because the directors were reluctant to share the spoils by raising more capital that would dilute their shareholdings.

The directors did a small placement of new shares to insiders at $5 per share in December 1969, well below the market price of $110 at the time. The sheer scale of director and broker skulduggery was breathtaking.

There actually was a mine and it actually did produce nickel!

Unlike most of the new mining ventures floated in the boom, Poseidon did actually have a mine with nickel in it.

After Poseidon ran out of money and collapsed, the mine was taken over by Western Mining in 1974. Western Mining had discovered nickel further south at Kambalda, WA, in 1966 and was the largest WA nickel miner at the time.

(In 2002, Western Mining’s bauxite/alumina business was renamed as Alumina Ltd (ASX:AWC, still trading today at a fraction of its 2002 price), and the rest of WMC was bought by BHP in 2005.)

The Mt Windarra mine eventually produced 5 million tonnes of ore (for Western Mining), yielding 80,000 tonnes of Nickel. The problem was that by that time, nickel price was just £1,530/ton.

At low nickel prices, the mine was unprofitable, so it was mothballed in 1989 - where it sat for the next thirty years, waiting for the nickel price to rise to a level that might make it profitable.

Recent 2021-2 nickel boom-bust

When nickel prices eventually recovered, a company called Poseidon Nickel picked up the mothballed Mt Windarra nickel mine and tried to jump on the bandwagon to take advantage of the surging nickel prices.

The 2021-2 price surge was triggered, once again, by lags in exploration due to the previous glut, plus supply restrictions (this time Covid), and government policy changes (Indonesian export ban).

The recent nickel bubble ended the same way as the last one, for the same reasons – over-supply from new mines, this time mainly in Indonesia, and new technology that enabled lower grade laterite ores to compete with higher grade Pentlandite sulphides.

Today (March 2024) the nickel price at US$18,500 is barely higher than it was at its 1969 peak price (£6,910 or US$16,500 / ton in November 1969), 55 years ago. And that’s before inflation.

After inflation, the nickel price is down by more than 80% since its 1969 peak. Who says commodities are an inflation hedge?

In the 54 years from 1969 to 2023:

- · the world population has grown 2.2-fold = 1.5% pa

- real world GDP (ie total demand and spending) has grown 5.3-fold = 3.1% pa

- but nickel production has risen by 9-fold = 3.6% pa

- Supply growth has swamped demand growth, so nickel prices have fallen in real terms.

Never underestimate human ingenuity to find more stuff!

There is always more stuff in the ground we don’t even know about yet.

And there are always going to be unknown future technologies and scientific breakthroughs that will make more remote ores and lower grade ores accessible

So commodities prices are always going to crushed by supply exceeding demand.

We have only just begun to scratch the surface of Australia, and the rest of this vast planet.

Cycles in investor euphoria and losses

Just like in the late 1960s nickel bubble, countless thousands of investors saw prices rising and jumped into the recent nickel boom in 2021-2 – driven by mass hysteria and mass ‘FOMO’ and the hope that ‘this time is different’.

Then when prices collapsed, as they always do, they were left wondering where their money went, and whether they will ever get it back.

Lessons

The main lesson is that mining boom-bust cycles (along with investor fear & greed cycles) follow a familiar pattern. Only the details are different in each case.

Most people tend to focus on the demand side of the mining equation (eg. growth in China, growth in the EV market, etc), but most of the reasons for price surges and collapses are usually on the supply side.

- Over-production and under-investment from the previous collapse mean supply growth lags demand growth, so commodity prices start to rise, often accompanied and accelerated by a supply restriction (strike, Covid lockdown, mine disaster, change in government policy, etc).

- Explorers see prices rising and suddenly start to ramp up exploration and re-open old mines or higher cost mines that were closed years ago when prices fell in the last bust.

- At the same time, rising prices lead buyers of the commodity (stainless steel manufacturers or batteries today) seek out and find cheaper alternatives and substitutes.

- New technologies and techniques also open up access to deeper and/or lower grade ore, further flooding the market with supply.

- Due to time lags between exploration and mine development/re-opening, new production from the new and re-opened mines finally come on stream, flooding the market and over-taking demand, sending prices lower.

- With over-supply and low prices, miners close mines and stop exploration, so the whole cycle starts over again.

Never buy anything merely because the price is going up, or because ‘everybody else is doing it!’ Never follow the crowd.

Take a step back and get a picture for where we are in the cycle, focussing most attention on the supply side.

Further reading:

Since Uranium prices are rising nicely in a new bubble, see:

Case Study: Lessons from the 2003-7 Uranium-Paladin Bubble & Bust

For a detailed account of the late 1960s mining boom in Australia, and the subsequent collapses in the early-mid 1970s – see:

Sykes, Trevor, 1970, “The Money Miners: The Great Australian Mining Boom”, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1978, 1995.

For a full run-down on the mining boom in Australia in the late 1960s, including the collapses, losses, and legislative outcomes, see:

The ‘Rae Report’ – Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Securities Markets and Their Regulation – Report from the Senate Select Committee on Securities and Exchange - AGPS, 1974

'till next time - happy investing!

_______________________________________________________________________

Disclosure: I have been a shareholder in mining companies from time to time. Currently I have no shares in companies in which the exploration, mining or processing of nickel or other battery metals is a significant part of their operations, other than possible minor exposures through broad index funds.

As always, my analysis is fact-based and intended to be as dispassionate as possible, regardless of whether or not I am a buyer, a seller, or holder of any security or asset. This quick, initial snapshot is no substitute for more detailed research.

This is intended for education and information purposes only. It is not intended to constitute ‘advice’ or a recommendation to buy, hold, or sell and stock or security or fund. Please read the disclaimers and disclosures below.

_______________________________________________________________________