Virgin Airlines is in the news again. It is being tarted by shifty private equity tricksters hoping to lure another batch of gullible investors into parting with their hard-earned cash - again.

Before getting into the merits of Round 2, it’s worth taking a look at what happened in Round 1.

What are the lessons from the last sorry tale? Has anything changed?

Double failure last time

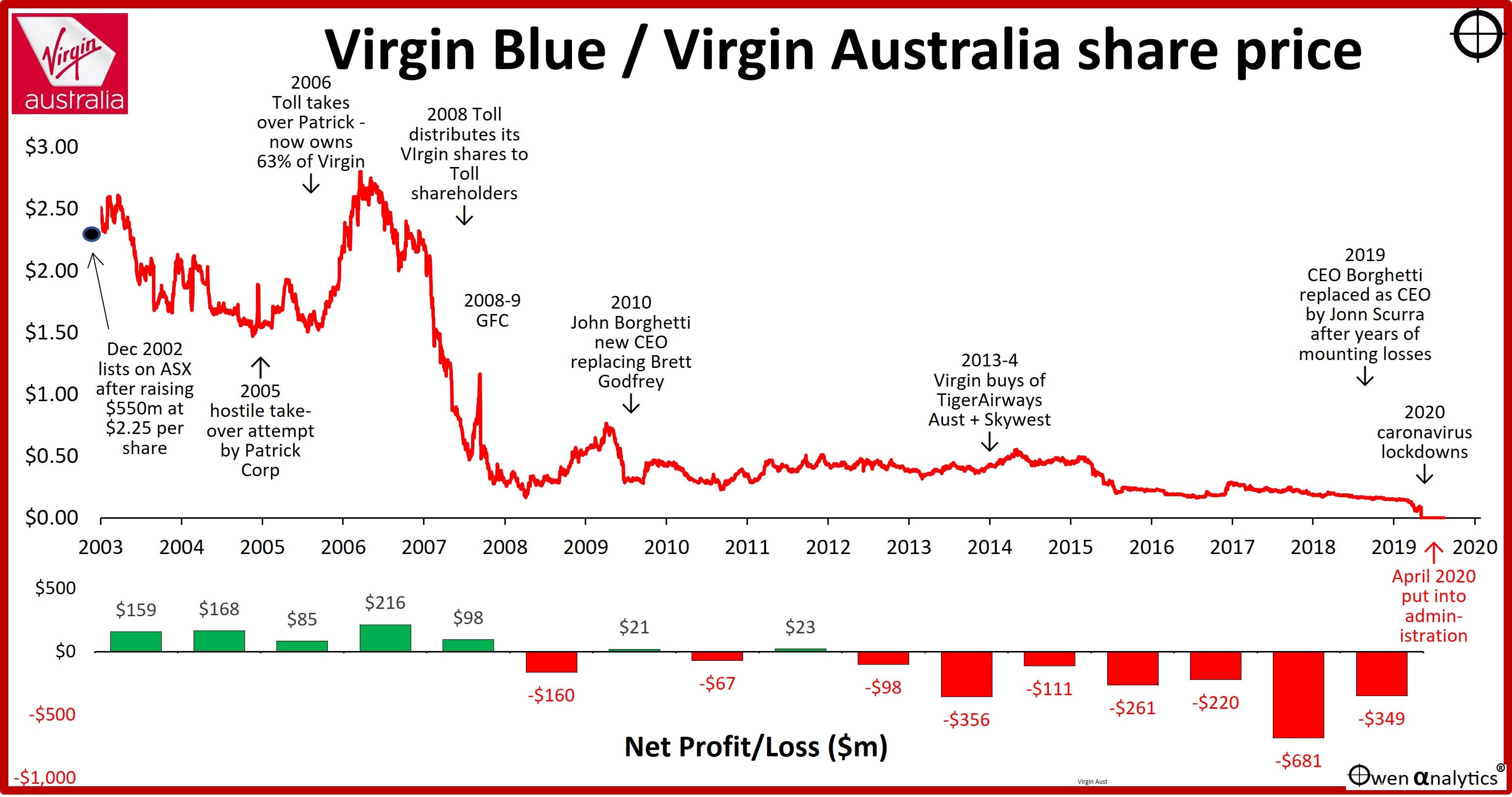

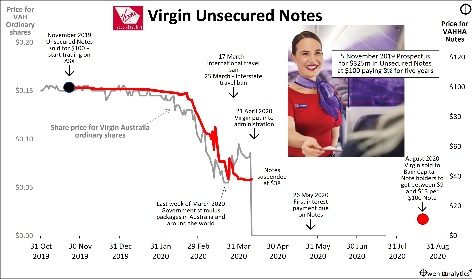

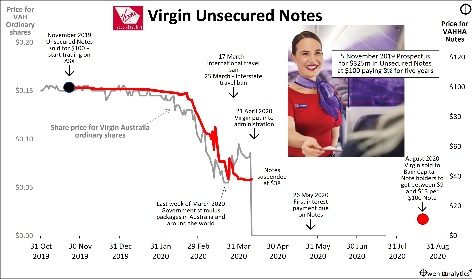

The Virgin Airlines experiment in Australia was a costly double failure for investors - not only for owners of the $550m worth of ordinary shares raised in the 2002 IPO, but also for the retail investors who bought $325m in ASX-listed retail bonds that Virgin used to raise last-minute emergency debt just four months prior to its collapse.

Here is my story on that sory saga -

Australia – perennial graveyard for commercial airlines

Australia’s vast distances and sparse population has made it a perennial graveyard for commercial airlines. There have been literally hundreds of different airlines over the past century that have tried to make a go of it here - mostly tiny operations, but also a number of large, high-profile failures.

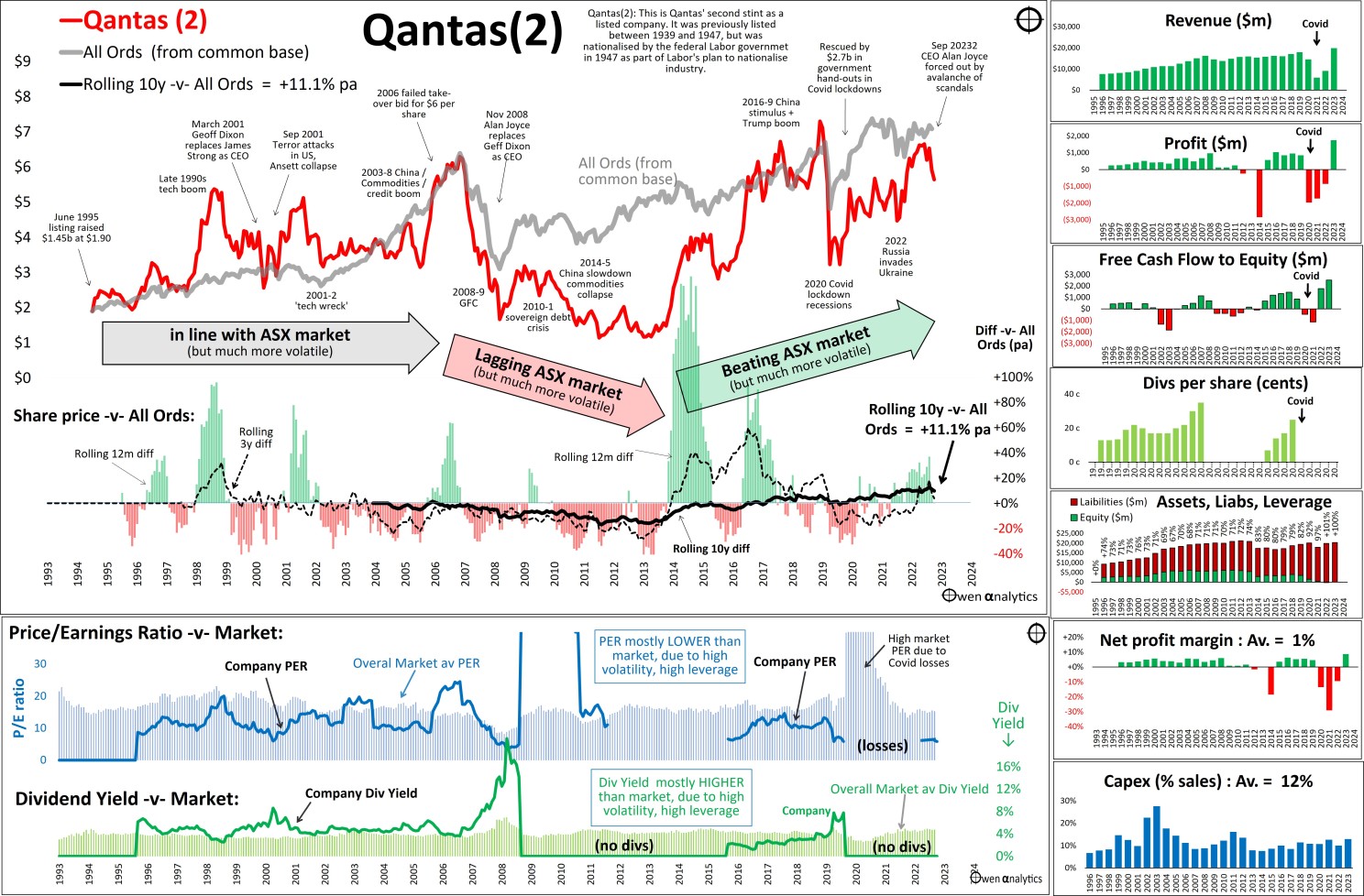

All have ultimately failed except for the former government-owned and still government protected national carrier, Qantas.

See: Qantas – My adventure with the over-geared, over-protected, cash-less bird! (6 Sep 2023)

Virgin at birth

‘Virgin Blue’ was started in 2000 by British serial entrepreneur Richard Branson and initial CEO Brett Godfrey (ex-Virgin Atlantic and Virgin Express in Europe). The plan was that the local Virgin operation was going to be a no-frills, low-cost, budget airline to try to compete in Australia’s domestic market with the two entrenched incumbents, Qantas and Ansett.

It was always going to be tough for a new start-up airline, but Virgin did have the advantages of Branson’s ‘Virgin’ brand and also the general euphoria surrounding the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games.

Early surge after Ansett collapse

Virgin got an immediate boost when Ansett collapsed a year later in September 2001, and Virgin quickly grew to take up to 30% share of the domestic market.

The wily Branson, and equally wily Chris Corrigan, who was CEO of Patrick Corp which owed 45% of Virgin, took advantage of the early success and decided to raise money from the public and list Virgin on the ASX. The public float raised $550m at $2.25 per share and the shares started trading on the ASX in December 2002.

Peaked early

Unfortunately, that was pretty much the peak, and it was virtually all downhill from there.

Government-protected national carrier Qantas was never going to let a new upstart steal market share. Qantas hit back in 2003, launching its 100%-owned budget subsidiary, Jetstar, run by Alan Joyce. (Joyce was so successful in destroying not only Ansett and later Virgin, he was promoted to CEO of Qantas, where he thoroughly trashed Qantas’ once-world-class reputation and once-loyal customer base, while lining his pockets royally).

A price war broke out and it hurt all players. The only winner in a price war is the player with the deepest pockets, and that was always going to be the government-protected Qantas.

Patrick Corp attempted to change Virgin’s strategy by trying to take control of the airline in a hostile take-over bid in 2005. Patrick ended up with 63% of Virgin’s shares but Patrick itself was taken over by Paul Little’s Toll Holdings in 2006. Toll didn’t like what they saw either, so it got rid of its Virgin shares by distributing them as free ‘gifts’ to Toll’s shareholders in 2008. This left Branson as the largest shareholder of the airline, with 25%.

Going up-market

In 2010, with losses mounting up, Virgin gave up on its failing low-cost strategy and replaced its initial CEO Brett Godfrey with John Borghetti from Qantas. Borghetti had been passed over for Qantas CEO (for Joyce) and he spent the next decade taking Virgin up-market and trying to compete head-on with Qantas as a full-service domestic and international carrier.

Godfrey changed the name to Virgin Australia, brought in fancy things like business class seats, in-flight service, airport lounges, and greatly extended international flights. Virgin also bought Tiger Airways Australia as a budget carrier, and SkyWest for regional routes.

All of this was very expensive and Virgin’s losses kept mounted up. After years of big losses with no end in sight, CEO Borghetti had to go. He was replaced in 2019 by new CEO Paul Scurra (also ex-Qantas, and experience at Ansett, Flight Centre, then Queensland Rail, and DP World).

The more passengers it carried, the more money it lost!

But it was all too late. Even before the 2020 coronavirus hit, the company was in deep trouble, with huge debts and skinny margins. In its first 6 years of operation to 2008, the company had made a total of $800m in profits, but then it lost a total of $2.5b over the next 12 years to 2019.

Passenger numbers had been rising steadily each year, but the more passengers Virgin carried, the more money it lost! Essentially it was buying loss-making passengers, with debt. By 2019 it had a debt/equity ratio of almost 1,000% - and that was just on-balance-sheet debt!

Covid

Then the coronavirus hit in 2020, and the government-mandated travel lockdowns brought flights to an immediate standstill. The fleet was grounded in March 2020 and the company searched around for a bailout.

Virgin sought a $1.4b loan from the federal government but was knocked back, as the government didn’t want to create a precedent for bailing every other company that put its hand out.

Virgin was not an Australian ‘champion’ like Qantas. It was 90% owned by foreigners, including 40% Chinese. The foreign owners included HNA (China, which bought Air NZ’s stake), and Nanshan (China) with 20% each, plus Singapore Airlines, Etihad (United Arab Emirates), and Branson had 10%, having wisely sold down earlier.

The public shareholders owned only 10% of the company. So there was no appetite for Australian tax-payers to bail out a bunch of foreign airlines who refused to tip in more cash to keep the thing alive.

Death

In April 2020 Virgin was put into administration, owing $6.8b to 12,000 creditors. The shareholders were wiped out completely and in September 2020 the creditors agreed to a debt restructure and sale of the remnants to US private equity group Bain. Bain’s plan was to have another shot, without the old shareholders, and free of most of the debt.

The virus lockdowns did not kill Virgin. It was killed by overly aggressive, debt-funded expansion, and attempting to win a price war against a well-entrenched incumbent that was a protected, politically connected dominant player in its home market.

Virgin was never going to last long without continuous injections of capital to keep it alive. It was highly vulnerable to any hiccup. Covid was just the final straw. It was a dud from day one.

Round 2?

The only IPOs I ever invested in were my own (when I am a seller, not a buyer, in the mid-1980s take-over boom prior to the 1987 crash, and in the late 1990s ‘dot-com’ boom prior to the 2001-2 ‘tech wreck’). I have never invested in other people’s IPOs.

That’s not to say I never will in the future. It’s not a rule I have, just an outcome of doing research into hundreds of IPOs I have looked at over the past four decades. The vast majority of IPOs disappear worthless almost as quickly as they appear, but there are a few good ones every once in a while.

This means that I have missed out on some genuinely good IPOs over the years, but have also avoided hundreds of duds.

I’m looking forward to seeing the prospectus for Virgin round 2 for a bit of light relief!

Who needs fiction?

My friends know that I never read fiction.

Who needs fiction when you have IPO prospectuses and company annual reports to read? They are packed full of more fanciful nonsense that even the best fiction writer could ever make up!

(Never EVER read the first half of prospectuses or annual reports, which are full of pretty pictures and fluff designed by clever marketing folk to cover up the true story. Just tear it out and go straight to the good stuff - the numbers. That's where the real fun starts).

Here is my story on the equally sorry saga of the Virgin Notes, where Virgin raised an additional $325m from retail punters right before its collapse. They lost the lot as well.

‘Till next time – happy investing (and be wary!)

Thank you for your time – please send me feedback and/or ideas for future editions!